An Agent Based Model to look at Gwent Pro Ladder (results)

let's dive into the data the ABM generated

With the Agent Based Model (ABM) from the previous post we can simulate any number of Gwent players, with known skill and play rate, playing throughout a season. Using this model we’ll try to get a firmer grasp on the ladder system and test whether this rewards skill or grinding games…

Climbing Pro Ladder Skill vs Grind

The ABM mimics a population of agents playing Gwent for an entire season with different innate skill and time to play. Though unlike with actual people we can change the parameters of the model to examine what we want to test. So in the first model we’ll disable any kind of learning, where agents would get better as they play more games, to see only the impact of playing more games on the peak MMR score (of a single faction).

To do this a model was run with these parameters:

- 8000 players

- 100 steps resulting in players playing 25-170 games per season

- no learning players don’t get better by playing more games

- initial skill ranges from 1200-2700 distributed similarly as chess players

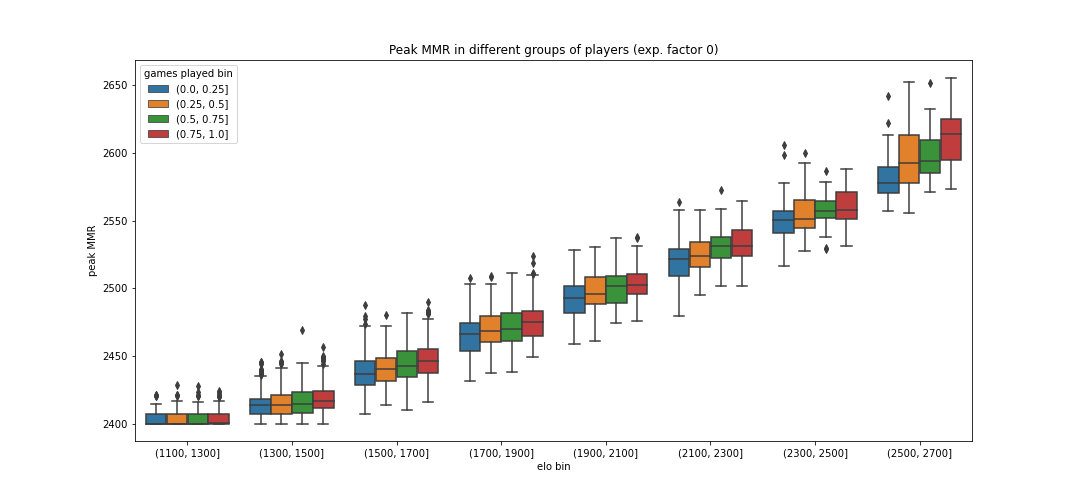

After running the model with these parameters, we can group players by skill (in bins of 200 ELO) and amount of games played (in 25 percentile bins). Then we can plot out their peak MMR and see how well they did. The resulting graph (shown below) immediately reveals two flaws with the current system. The spread within a group of players with similar skill, that played a similar number of games is quite large. Simple luck of when you play your games and who you queue into can make a difference of up to 70 MMR! Furthermore, players that play more tend to acquire a higher peak MMR than players with similar skill that play fewer games. Therefore players able to put in more games each season have a distinct advantage over those with less time on their hands.

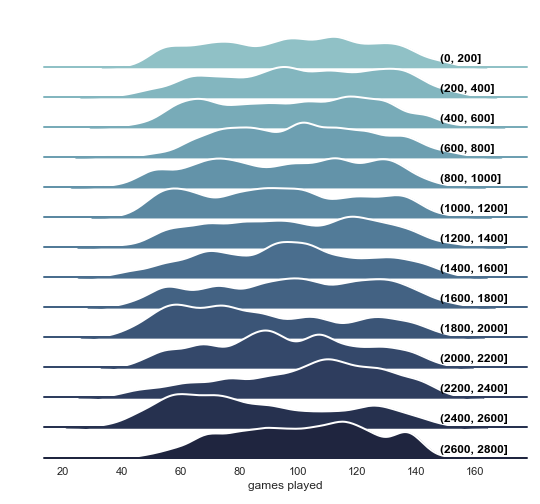

When looking at actual data, it became obvious that players in the higher ranks tend to play more than players further down. When recreating this plot with the simulated data, this pattern doesn’t appear. This will be discussed further down in the article.

Adding Learning to the Model

We can reasonably assume that as a player plays more games their familiarity with the deck they are playing and the

meta are increasing. Simply put, they get better at the games by playing more games. Perhaps this can explain the

increase in players with a lot of games under their belt at the higher positions? To test this an experience factor is

added to the model which gives players an ELO bonus as they play more games defined. A new model was run with this

learning factor set to 20, as the ELO bonus is calculated as experience_factor * sqrt(games_played) this would give

a player that played 100 games a 200 ELO increase over a player that played none even if their innate skill was the same.

As other parameters were left the same, for this simulation these settings were used:

- experience factor 20

- 8000 players

- 100 steps as before

- initial skill ranges from 1200-2700 with the same distribution as the previous

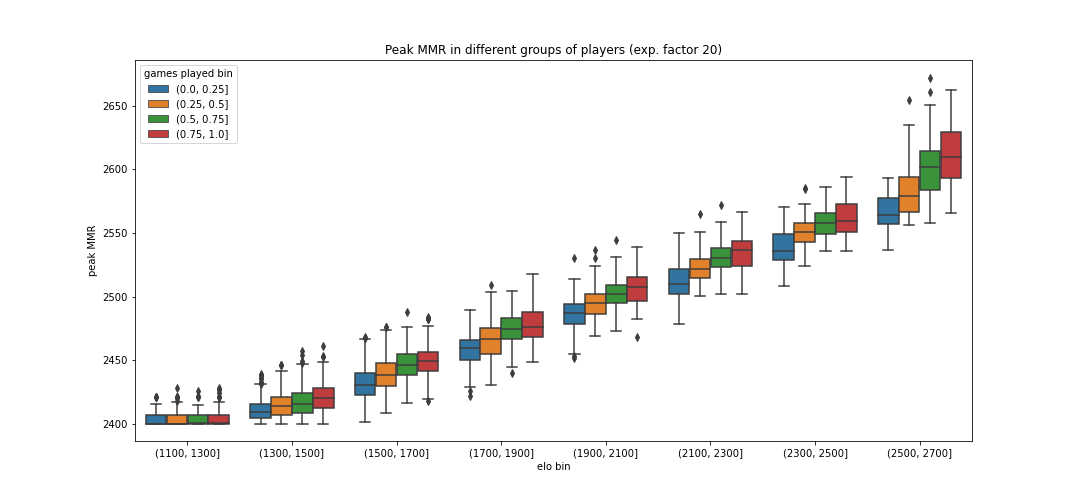

Now the same plot can be created showing the peak MMR of the agents grouped by innate skill and the number of games they played. As agents now learn by playing games the difference in peak MMR between players that play little and those that play a lot, despite starting at a similar skill level, increases.

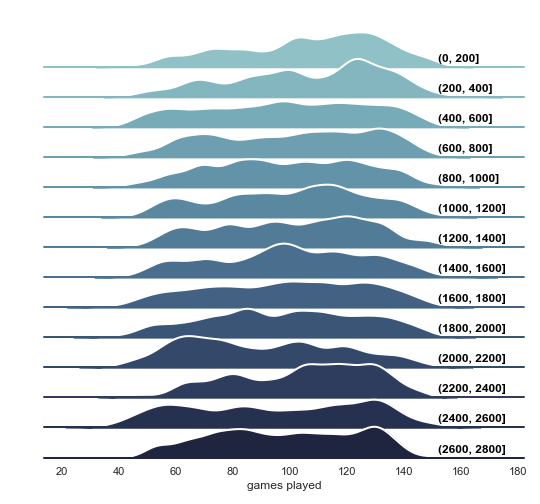

To check if with agents learning, as you would expect from actual players, those that play more frequently shift to higher ranks the same ridgeline plot was created. There is a minor shift, but it is barely perceptible and nowhere near the clear shift that is observed in real data.

Even with the experience factor pushed to 100 (data in repository), which is far beyond the skill increase you can expect in real life, this pattern cannot be replicated. There is another factor at play here, one that is not included in our model…

Discussion

Using a model we can check a number of things which cannot be easily tested in real life, and this reveals a few things about how the ladder system works. With an Agent Based Model we know exactly what the innate skill is of each agent and we can check how high up the ladder they can get in a number of games. So we can quantify how well ladder is at ranking individuals based on their actual skill. Also the impact of playing more games could be uncovered both with players getting better by playing more games in the absence of any learning.

Will Playing More Games Get You Higher Up?

Answer: Yes, but not much

Playing more games gives you a relatively small advantage over players that play fewer games, even in the absence of a player getting better by playing more games. However, this advantage isn’t big enough that an average player will suddenly be able to get into the Top 200 or even the Top 500 simply by playing a ton of games.

As a matter of fact, there is a lot of variance between innate skill and peak MMR reached. By playing 30-50 games and being lucky with who you queue into, you could end up at 50 MMR higher than an equally skilled player that plays two or three times more games but has worse luck.

Why Are Players Higher Up Playing More ?

Answer: Human psychology ?

Players that play more don’t simply end up higher in the ranks because they play more. No amount of learning can account for the shift that is observed in real data. So human players exhibit behaviour that doesn’t emerge from the model. I’ll go out on a limb and give a few hypotheses which could explain this discrepancy between the model and observation.

- Players that were playing a lot in previous seasons will be (i) more proficient at the game due to experience and (ii) will continue to do play the game more than average.

- While the gains are relatively small, the way ladder works gives a small advantage to frequent players. The higher up ladder you get the more competitive it gets and more players are willing to play additional games to leverage this minor edge over their competition.

- Players in higher ranks notice that other players at their level play more. Therefore there is a push to keep up the pace.

- A combination of all of the above … there probably isn’t a single explanation that applies to all players

Is There a Need to Grind ?

Answer: Yes, at higher ranks

Playing more games gives you an advantage and this advantage becomes bigger within the most skilled groups of players. That taken together with the fact players in those groups tend to play quite a few games each season, you lose that edge unless you play even more … This is a feedback loop where players might feel compelled to play more than they would otherwise. Even though that edge isn’t big, a small difference in MMR in that relatively small pool of top players could mean the difference between a top 200 spot, crown points and a spot in an official tournament or missing out on all that.

Is Peak MMR a Good Metric ?

Answer: It can be improved

Peak MMR as a metric is reasonably well correlated with the innate skill of a player, so overall it does a fair job capturing the skill of a player. Though there are two main issues that emerged from this analysis:

- There is a lot of variance, similarly skilled players that play roughly the same number of games can end up with peak MMR scores that are up to ~70 point apart. This is simply based on luck and who you queue into.

- Playing more leads to higher peak MMR scores, even in the absence of learning. Having a winning streak at the right time can push the peak MMR score up. Playing more games increases the chance of such a streak happening at the right moment.

Because the simulation assumes players are playing with a single faction, and Gwent sums up the MMR scores for your four best factions this reduces variance as having luck with one will be cancelled out by having bad luck with another. This could be further improved by recalculating MMR each 5-10 games, similar to how calculations are done to adjust ELO scores for Chess players at the end of a tournament.

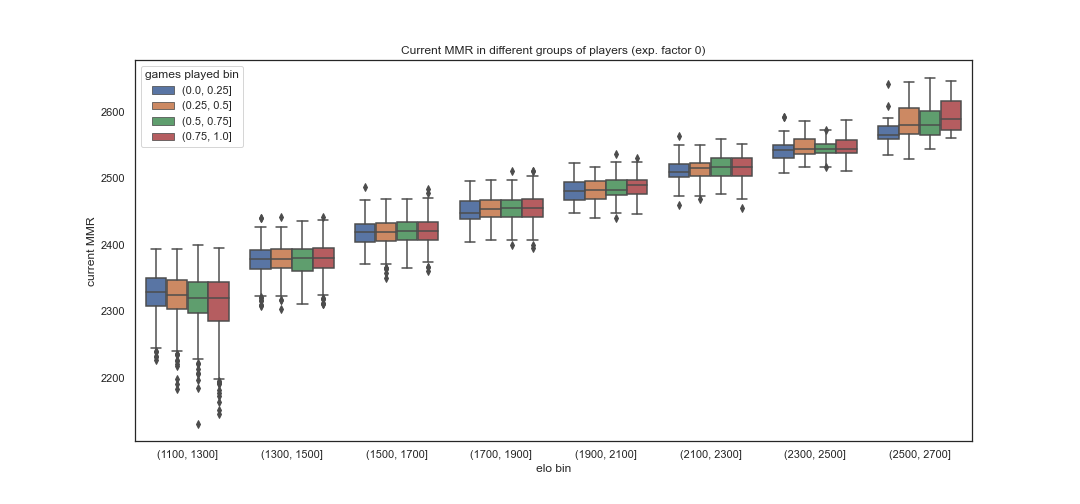

The impact of playing more games is very easy to get rid of … by ranking based on the current MMR instead of the peak MMR. As you can see in the graph below, in the absence of learning, when considering current MMR there is no difference between players with comparable skill based on the number of games they play.

Peak MMR creates an incentive to play as many games as possible, and gives players the option to play more leisurely once they no longer wish to climb with a certain faction. Therefore this cultivates a more active player base. The current MMR would not allow players to start playing more casually in ranked as this would lower their score again. Once you reach an MMR that feels like it would be a peak for you, it would actually be better to stop playing that faction for the remainder of the season. This would mean fewer people are active and queue times would increase making that part of the game worse.

Conclusion

No, you can’t grind your way to a top 200 spot unless you have the skills to get there. Though playing more games than your competitors with similar skills is an advantage. In the top brackets where players play fairly frequently this would mean playing even more games to use that as a competitive advantage.

Should peak MMR be replaced by current MMR as the metric? As a game developer CDPR likely wants as many people online playing as possible, and using peak MMR to measure ladder performance aligns well with that. However, this incentivises players to play more and competitive players to not only compete to play their best, but also as much as possible. In an age where digital wellbeing is starting to show up on the agenda of companies like Google, Samsung and Apple, this is something CDPR might need to have a look at sooner or later.

Liked this post ? You can buy me a coffee