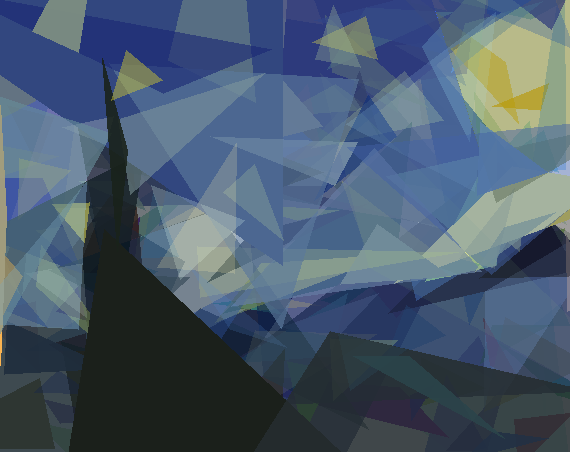

Genetic algorithms are fun, they require a different way of thinking. Here I’ll guide you through my process of building an algorithm that evolves 150 random triangles into a famous piece of art. The work I picked to re-draw: Van Gogh’s The Starry Night. The original and the version the algorithm created after 5000 generations are shown below.

The code for this post can be found on GitHub here

Update 25/03/20201: There was a change in the Evol API in version 0.5.2 where the function apply() has been

renamed to callback(), the code here and in the repository has been updated.

Genetic algorithms

Before we start, a quick word about genetic algorithms. There is a rather lengthy description on WikiPedia, but here we’ll keep it short and simple. These algorithms are heavily based on biological principles of inheritance, breeding and evolution. You have a number of solutions, called the population. Each individual solution having a list of items, values, … called the chromosome. There is a fitness function to assess how good a certain solution is for our problem. Within this population, individuals can be removed (the ones with the worst fitness), they can breed (combine their chromosomes into a new individual), and mutate (introduce random changes to the chromosome).

In this context:

- the population is a collection of 200 paintings

- each individual is a single painting

- the chromosome is a list of 150 triangles with a certain shape, position and color (red, green, blue and opacity)

- the fitness is the distance (based on pixels) from the target painting (we need to minimize this score)

- individuals can breed, create a new painting with half of the triangles from one parent and half from the other

- individuals can mutate, triangles can move, change shape, change color, swap position in the chromosome or reset

- the population can go through a bottleneck, where a large portion of individuals (with the worst fitness) is discarded and then the survivors are used to grow the population back to the desired size

Implementing the algorithm in Python

Coding all steps yourself wouldn’t be that difficult, though the Evol provides a great API that takes care of all the scoring, breeding, … and has multi-processing build in for calculating the finess of each individual in a population.

The triangle class

A chromosome here is a list of triangles. A single triangle has three point with x,y coordinates and a color with

opacity. A few different changes can occur during a mutation, the triangle can move (shift all points), change shape (move points

individually) or the color can change. There also is a more significant event that will destroy the current triangle and

replace it with a totally random one. This is all taken care of by the .mutate function. The sigma value can be used to

specify the strenght of a mutation (how strong the change will be) and the weights are used to specify which types of

mutation will occur more often than others.

import random

class Triangle:

def __init__(self, img_width, img_height):

x = random.randint(0, int(img_width))

y = random.randint(0, int(img_height))

self.points = [

(x + random.randint(-50, 50), y + random.randint(-50, 50)),

(x + random.randint(-50, 50), y + random.randint(-50, 50)),

(x + random.randint(-50, 50), y + random.randint(-50, 50))]

self.color = (

random.randint(0, 256),

random.randint(0, 256),

random.randint(0, 256),

random.randint(0, 256)

)

self._img_width = img_width

self._img_height = img_height

def __repr__(self):

return "Trangle: %s in color %s" % (','.join([str(p) for p in self.points]), str(self.color))

def mutate(self, sigma=1.0):

mutations = ['shift', 'point', 'color', 'reset']

weights = [30, 35, 30, 5]

mutation_type = random.choices(mutations, weights=weights, k=1)[0]

if mutation_type == 'shift':

x_shift = int(random.randint(-50, 50)*sigma)

y_shift = int(random.randint(-50, 50)*sigma)

self.points = [(x + x_shift, y + y_shift) for x, y in self.points]

elif mutation_type == 'point':

index = random.choice(list(range(len(self.points))))

self.points[index] = (self.points[index][0] + int(random.randint(-50, 50)*sigma),

self.points[index][1] + int(random.randint(-50, 50)*sigma),)

elif mutation_type == 'color':

self.color = tuple(

c + int(random.randint(-50, 50)*sigma) for c in self.color

)

# Ensure color is within correct range

self.color = tuple(

min(max(c, 0), 255) for c in self.color

)

else:

new_triangle = Triangle(self._img_width, self._img_height)

self.points = new_triangle.points

self.color = new_triangle.color

The painting class

The painting contains a list of Triangles, along with the necessary functions to draw the triangles (using the Pillow library) and to compare the image with the target (using the Imagecompare library). Furthermore, there is a function to mate two paintings, this is inspired by crossing over events in biology where two chromosomes exchange parts to create two new chromosomes.

from triangle import Triangle

from random import shuffle, randint

from PIL import Image, ImageDraw

from imgcompare import image_diff

import random

class Painting:

def __init__(self, num_triangles, target_image, background_color=(0, 0, 0)):

self._img_width, self._img_height = target_image.size

self.triangles = [Triangle(self._img_width, self._img_height) for _ in range(num_triangles)]

self._background_color = (*background_color, 255)

self.target_image = target_image

@property

def get_background_color(self):

return self._background_color[:3]

@property

def get_img_width(self):

return self._img_width

@property

def get_img_height(self):

return self._img_height

@property

def num_triangles(self):

return len(self.triangles)

def __repr__(self):

return "Painting with %d triangles" % self.num_triangles

def mutate_triangles(self, rate=0.04, swap=0.5, sigma=1.0):

total_mutations = int(rate*self.num_triangles)

random_indices = list(range(self.num_triangles))

shuffle(random_indices)

# mutate random triangles

for i in range(total_mutations):

index = random_indices[i]

self.triangles[index].mutate(sigma=sigma)

# Swap two triangles randomly

if random.random() < swap:

shuffle(random_indices)

self.triangles[random_indices[0]], self.triangles[random_indices[1]] = self.triangles[random_indices[1]], self.triangles[random_indices[0]]

def draw(self, scale=1) -> Image:

image = Image.new("RGBA", (self._img_width*scale, self._img_height*scale))

draw = ImageDraw.Draw(image)

if not hasattr(self, '_background_color'):

self._background_color = (0, 0, 0, 255)

draw.polygon([(0, 0), (0, self._img_height*scale), (self._img_width*scale, self._img_height*scale), (self._img_width*scale, 0)],

fill=self._background_color)

for t in self.triangles:

new_triangle = Image.new("RGBA", (self._img_width*scale, self._img_height*scale))

tdraw = ImageDraw.Draw(new_triangle)

tdraw.polygon([(x*scale, y*scale) for x, y in t.points], fill=t.color)

image = Image.alpha_composite(image, new_triangle)

return image

@staticmethod

def _mate_possible(a, b) -> bool:

return all([a.num_triangles == b.num_triangles,

a.get_img_width == b.get_img_width,

a.get_img_height == b.get_img_height])

@staticmethod

def mate(a, b):

if not Painting._mate_possible(a, b):

raise Exception("Cannot mate images with different dimensions or number of triangles")

ab = a.get_background_color

bb = b.get_background_color

new_background = (int((ab[i] + bb[i])/2) for i in range(3))

child_a = Painting(0, a.target_image, background_color=new_background)

child_b = Painting(0, a.target_image, background_color=new_background)

for at, bt in zip(a.triangles, b.triangles):

if randint(0, 1) == 0:

child_a.triangles.append(at)

child_b.triangles.append(bt)

else:

child_a.triangles.append(bt)

child_b.triangles.append(at)

return child_a, child_b

def image_diff(self, target: Image) -> float:

source = self.draw()

return image_diff(source, target)

Putting the algorithm together

The Evol package will take care of most of the work for use, but we do need to define a couple functions to get started. We will have a score function, that checks the distance to the target image. A function how individuals will find a partner to mate with and define how we wish to evolve the population. We’ll also add a function to print the fitness scores (so we can see if there is still progress), that stores the image of the best individual and that stores the population every fifty generations (so we don’t have to start over again if something goes wrong).

from PIL import Image

from evol import Evolution, Population

import random

import os

from copy import deepcopy

from painting import Painting

def score(x: Painting) -> float:

"""

Calculate the distance to the target image

:param x: a Painting object to calculate the distance for

:return: distance based on pixel differences

"""

current_score = x.image_diff(x.target_image)

print(".", end='', flush=True)

return current_score

def pick_best_and_random(pop, maximize=False):

"""

Here we select the best individual from a population and pair it with a random individual from a population

:param pop: input population

:param maximize: when true a higher fitness score is better, otherwise a lower score is considered better

:return: a tuple with the best and a random individual

"""

evaluated_individuals = tuple(filter(lambda x: x.fitness is not None, pop))

if len(evaluated_individuals) > 0:

mom = max(evaluated_individuals, key=lambda x: x.fitness if maximize else -x.fitness)

else:

mom = random.choice(pop)

dad = random.choice(pop)

return mom, dad

def mutate_painting(x: Painting, rate=0.04, swap=0.5, sigma=1) -> Painting:

"""

This will mutate a painting by randomly applying changes to the triangles.

:param x: Painting to mutate

:param rate: the chance a triangle will be mutated

:param swap: the chance a pair of traingles will be swapped

:param sigma: the strenght of the mutation (how much a triangle can be changed)

:return: New painting object with mutations

"""

x.mutate_triangles(rate=rate, swap=swap, sigma=sigma)

return deepcopy(x)

def mate(mom: Painting, dad: Painting):

"""

Takes two paintings, the mom and dad, to create a new painting object made up with triangles from both parents

:param mom: One parent painting

:param dad: Other parent painting

:return: new Painting with features from both parents

"""

child_a, child_b = Painting.mate(mom, dad)

return deepcopy(child_a)

def print_summary(pop, img_template="output%d.png", checkpoint_path="output") -> Population:

"""

This will print a summary of the population fitness and store an image of the best individual of the current

generation. Every fifty generations the entire population is stored.

:param pop: Population

:param img_template: a template for the name of the output images, should contain %d as the number of the generation is included

:param checkpoint_path: directory to write output.

:return: The input population

"""

avg_fitness = sum([i.fitness for i in pop.individuals])/len(pop.individuals)

print("\nCurrent generation %d, best score %f, pop. avg. %f " % (pop.generation,

pop.current_best.fitness,

avg_fitness))

img = pop.current_best.chromosome.draw()

img.save(img_template % pop.generation, 'PNG')

if pop.generation % 50 == 0:

pop.checkpoint(target=checkpoint_path, method='pickle')

return pop

if __name__ == "__main__":

target_image_path = "./img/starry_night_half.jpg"

checkpoint_path = "./starry_night/"

image_template = os.path.join(checkpoint_path, "drawing_%05d.png")

target_image = Image.open(target_image_path).convert('RGBA')

num_triangles = 150

population_size = 200

pop = Population(chromosomes=[Painting(num_triangles, target_image, background_color=(255, 255, 255)) for _ in range(population_size)],

eval_function=score, maximize=False, concurrent_workers=6)

evolution = (Evolution()

.survive(fraction=0.05)

.breed(parent_picker=pick_best_and_random, combiner=mate, population_size=population_size)

.mutate(mutate_function=mutate_painting, rate=0.05, swap=0.25)

.evaluate(lazy=False)

.callback(print_summary,

img_template=image_template,

checkpoint_path=checkpoint_path))

pop = pop.evolve(evolution, n=5000)

The output

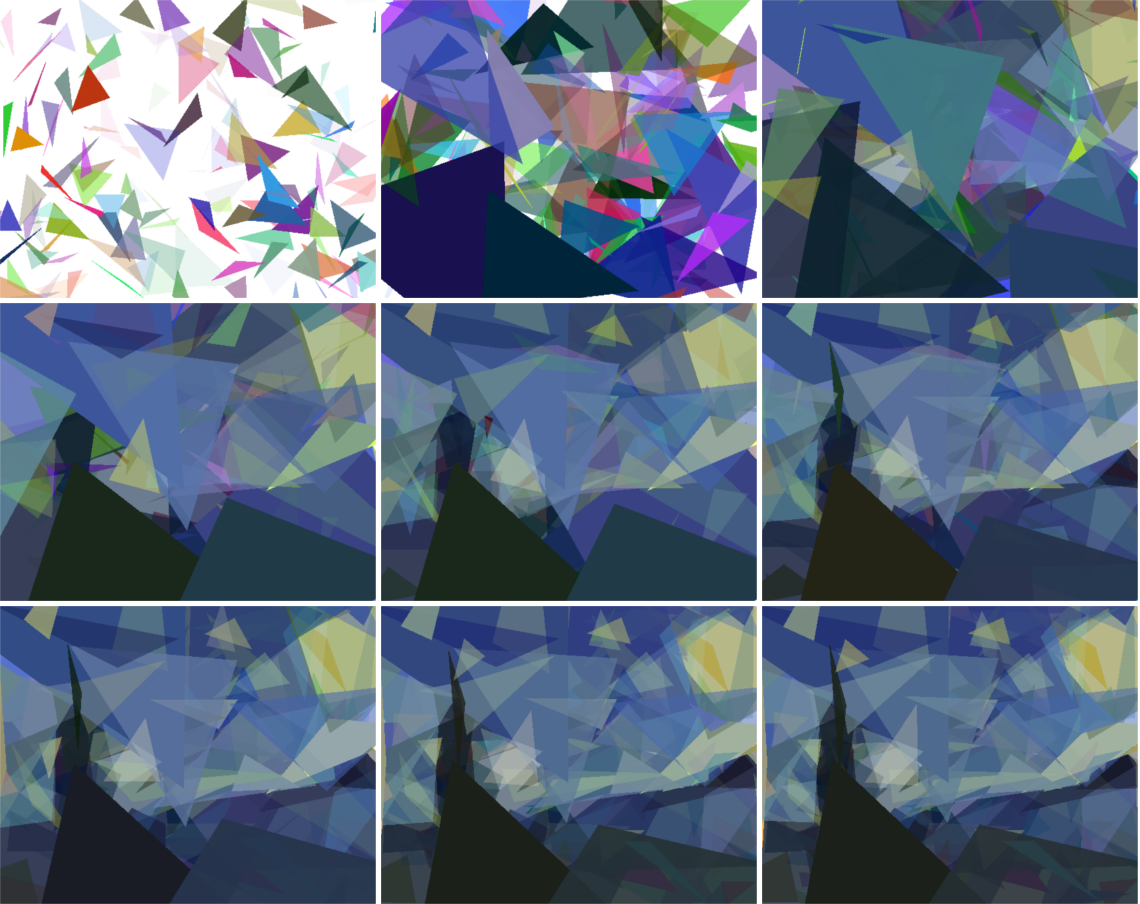

Here you can see the best individual from generation 1, 250, 500, 750, 1000, 1500, 2500, 3500 and 4500 (left to right, top to bottom).

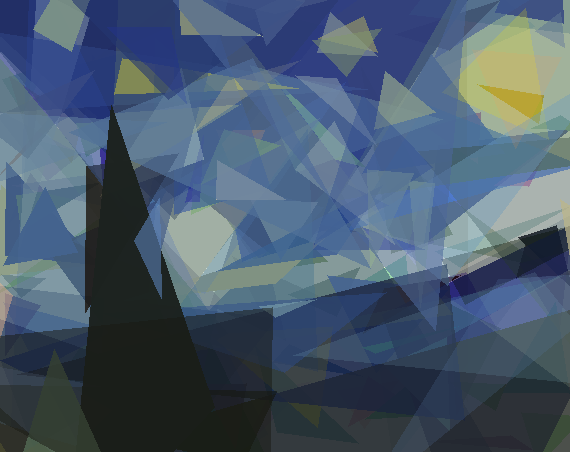

Different runs, different output

As the start of the evolution is random, as well as all mutations and breeding events, the output can differ between runs. Below you can see the result of two independent runs each running for 5000 generations. Even though these images have comparable distances to the target image, they are quite different from each other.

Conclusion & outlook

There results are quite cool, and since there is very little difference between generation 4500 and 5000 this is probably as good as it gets using only 150 triangles. There are a few things that could be improved though. The algorithm tries to match as many pixels correctly as possible. So matching pixels in large even spaces yields a much better score than getting details right. You could generate a mask, highlighting detailed areas, and rewarding correct pixels in those areas.

The chromosomes in this case are very static, they are always the same length (150 items) and apart from the occasional swapping of items nothing happens. In nature chromosomes evolve continuously in size and duplication of genes is often a source of innovation. The mutation function could be adjusted to add an extra triangle every so often or you could come up with more complex ways to mate paintings so lists of different numbers of items could be mated. However, adding additional triangles should come at a cost that should be taken into account for the fitness. In nature having a larger genome means copying more DNA each time a cell divides, so genomes cannot grow infinitely large. There needs to be a similar penalty to the fitness here. Tweaking this extra parameter could be difficult.

Finally, different styles could be used. Here using a limited number of triangles was used because it was the first thing that popped into my mind when starting this project. However, while working on this a few more (and potentially better) ideas emerged. These I’ll work out and I will cover them in a later post!

Liked this post ? You can buy me a coffee